The Finer Things In Life: a History of Thongs

Why this little strip of fabric tells a much bigger story

The dictionary defines thong as “a narrow strip of leather or other material, used especially as a fastening or as the lash of a whip”. By affinity, this word was appropriated to mean both the kind of sandals that are made of strips, and the type of underwear, also known as “G-string”, and its signature strip. The word thong comes into Old English via German, Zwang, meaning compulsion.

Ancient beginnings

According to the Fashion Historian Caroline Cox [1], this family of underwear is nothing more than a derivation of male underwear used in martial arts and sports for millenia. The most ancient form, which dates back to prehistory, is the Japanese Fundoshi [2], and this garment is still seen today in festivals and covering Sumō wrestlers. The concept is pretty straightforward: to cover and protect the genitals, while displaying the muscular power of the fighter.

Suzuki Harunobu, Arranging His Loincloth (circa 1770) from an untitled series, part of the Honolulu Museum of Art collection. Image: Public Domain.

Stage scandal

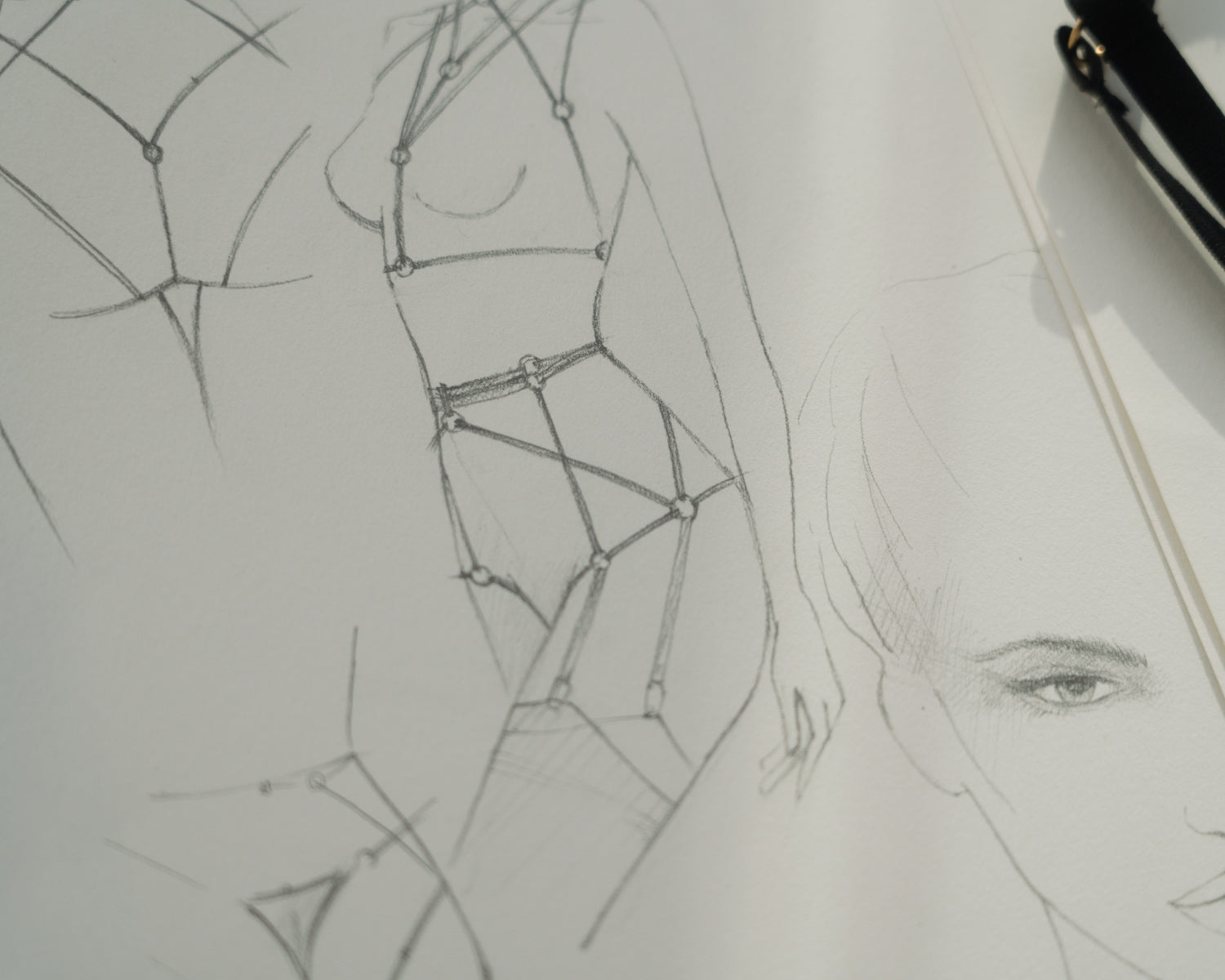

Prior to the 1990s, the thong as feminine underwear was worn primarily by exotic dancers; Caroline Cox speculates, though, that the thong we know today is not dissimilar to the “posing pouches” used by models in the Renaissance [3]: in essence, a drape of fabric used to cover the genitals while leaving the model’s buttocks exposed for the artists to draw. When thongs started to become popular in the 1980s, it was through controversial Pop stars, such as Madonna and Cher, who flaunted the garment on stage. The scandalous and controversial nature of this type of underwear marks its close affinity with the arts and the cult of the body.

Fashion historians [4] identify the thong’s first “public appearance” with an event in 1939, when the nude dances of New York were ordered by the mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, to cover up in respect of the visitors who were attending the World Fair. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the G-string was a mandatory item in the strippers’ wardrobe, as it enabled them to show as much as possible without crossing the hard taboo of displaying the labia in their dance acts. This element of scandal associated with thongs never came out of fashion, from the memorable appearances of the garment in popular culture (how to forget Samantha Jones’s “string of pearls” from Sex and the City!) to the moral panics, in the 2000s, about thongs being the cause of teenage girls becoming too sexualised, too soon.

On the sunny beaches of Cannes

Throughout their recent history, thongs were always misunderstood, and they always seemed to be too early in a world that wasn’t yet ready for them. In the first half of the 20th century, the fashion of G-strings didn’t take off, as most women considered them to be risqué or inappropriate. It was on the beach that thongs began to gain space as an “acceptable” garment. In 1946, the fashion designer Jacques Heim and the mechanical engineer Louis Réard both claimed the “invention” of the first bikini: the garment is part of the Metropolitan Museum collection [5], and consists of two triangles to cover the breasts, and two triangles, front and back, to cover the genitals. Far from being an “invention”—even though Heim and Réard claimed patents for the garment—the style had already appeared on the beaches of Cannes, where young women wore DIY versions of this swimming suit. Their goal? To get an even tan! The first “especially designed” thong bikini appeared in 1974, introduced by the fashion designer Rudi Gernreich [6]. While the invention was embraced by women of all sizes on the sunny beaches of Brazil—where the style called fio dental (yes, that means dental floss) is still almost synonymous with “bikini”—most women in the US and Europe weren’t ready to display their booties on the beach like that.

A billion-dollar industry

It was not until the 1980s that Victoria’s Secret made this style of knicker a sensation [7], leading them to become the fastest growing segment of the lingerie industry in the 1990s—so much so that, by 2003, the full-bottomed panties were almost “obsolete” [8], condemned to becoming the butt of a joke (pun unapologetically intended) in comedies such as Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001).

Although Sarah Tom Czak and Rachel Pask [9] unfairly classify the thong as “a historical snapshot revealing a time when women were prepared to do anything in the pursuit of beauty and sexual attraction”, the thong carries a much more complex cultural meaning. In the age of heavy and voluminous dresses supported by wired crinolines (that is, on and off, roughly between 1700 and 1900), underpants were not a “mandatory” item, and many ladies had naked bottoms under the cage [10]. Contradictorily, it is when fashion embraces an ideology of the “natural body”, through silhouettes that are closer to the skin, that the “layers of modesty” start to become a necessity.

Thongs became a definitive must-have in the 1980s when two cultural phenomena coincided: gym culture and its worship of muscular bodies, and the desire to display these carefully built figures through tighter and tighter trousers [11]. But it was also in the 1980s, especially through the American brand Frederick’s of Hollywood, that thongs—or the “scanty panty”—began to be sold as erotic items. The hype of the thong as a fetish is real, and it even played a pivotal role in the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal in the 1990s, when she admitted to “enticing” the president by lifting her skirt and showing the lines of her thong…

Le whale tail

The popularisation of thongs in the 2000s is largely due to celebrities such as Britney Spears and Mariah Carey and their donning of a G-string line above their low-rise jeans. That “ops” moment loved by paparazzi soon became an intentional style—so much so that luxury lingerie giants, such as Agent Provocateur, Frost French, and Gossard pioneered thongs that were intentionally designed to be displayed over the jeans, including lace, diamanté, and other decorations. Although the sales of thongs plummeted in the 2010s, the garment is making a comeback through Gen Z and their fascination with the 2000s as a “retro style”—among other fads, the “whale tail” is being spotted again, and even the extreme C-string is exiting the Brazilian Carnival straight into red carpet appearances!

Today

While full briefs or shaping shorts can provide the same functionality, the thong is an ode to our natural beauty and a cult of the uniqueness of each body as a work of art. Today, thongs dance in the narrow line separating the functionality of a uniform silhouette under a tight outfit and the worship of bottoms in strip-tease culture.

But for the Vivi Leigh woman, these two universes are not separated: the perfect foundation to display your beautiful body under an elegant silhouette can double as an ornament; when you undress, there is still that decoration, like a piece of jewellery expertly positioned to frame your derrière, adorning it without interfering with its shape and texture. The three black strips, both connected and disconnected by a little golden loop, are an enigma: they frame your hips, gently guiding the eyes through your curves and inviting the gaze to follow this little arrow, enticing the viewer to imagine what wonders lie at the end of this little line.

-Author: Dr Marilia Jardim

(Dr Marilia Jardim is a semiotician, researcher, and educator, MPhil in Communication and Semiotics and PhD in Communications and Media. Since 2012, her research focuses on fashion and the body and the socio-cultural narratives of dress and identity. As a lecturer, she has taught subjects on Communication, Culture, and Identity in Art, Design, and Creative Industries subjects for more than a decade and, in parallel, supported brands and businesses in branding and advertising through cultural research and commercial semiotics.)

Notes

[1] Caroline Cox, “G-string and Thong”, in. Valerie Steele (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, vol. 2, 2005, p 121-122

[2] “The Fundoshi and Japanese Male Fashion”, Yabai, available at: http://yabai.com/p/2213

[3] See Caroline Cox

[4] Idem, and Sarah Tom Czak & Rachel Pask, Panties. A Brief History, 2004.

[5] Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Timeline of Art History. The Bikini”, 2004, available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-bikini

[6] See Caroline Cox, and Sarah Tom Czak & Rachel Pask

[7] See Sarah Tom Czak & Rachel Pask

[8] See Caroline Cox

[9] See Sarah Tom Czak & Rachel Pask, p. 61

[10] see for example Farid Chenoune, Hidden underneath, 2005; Nina Edwards, The virtues of underwear, 2024; and Colleen Hill, 2014

[11] See Caroline Cox

References

Chenoune, F. 2005. Hidden underneath: a history of lingerie. New York: Assouline.

Cox, C. “G-string and Thong”, in. Steele, V. (Eds.) 2005. Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, vol. 2. New York: Scribner/Thomson, 121-122

Czak, S. T. & Pask, R. 2004. Panties. A Brief History. London: Dorling Kindersley.

Edwards, N. 2024. The virtues of underwear: modesty, flamboyance and filth. London: Reaktion Books.

Hill, C. 2014. Exposed: a history of lingerie. New York: Yale University Press with The Fashion Institute of Technology

MET “The Thong” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/91774

MET “Timeline of Art History. The Bikini”, 2004, available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/the-bikini

Yabai, “The Fundoshi and Japanese Male Fashion” 25th of July 2017, available at: http://yabai.com/p/2213